This post grew out of a recent facebook discussion. Hat Tip to Bruce Kunkel for the title phrase “Cognitive Prison Habits.”

George Monbiot recently made some important points and asked questions we all should be giving some thought to.

“Green consumerism, material decoupling, sustainable growth: all are illusions, designed to justify an economic model that is driving us to catastrophe.”

“The promise of economic growth is that the poor can live like the rich and the rich can live like the oligarchs. But already we are bursting through the physical limits of the planet that sustains us.”

I would add the aphorism that “When you find yourself in a hole, rule #1 is to stop digging.”

The International Energy Agency has just released their yearly World Energy Outlook report, which tells us that current policies put us in a scenario that would add the equivalent of another China and India to today’s global demand for energy by 2040, and greenhouse gas reduction polices currently in play or being considered are “far from enough to avoid severe impacts of climate change.”

While the title of Monbiot’s post mentions consumerism trashing the planet, consumerism is not the fundamental problem (us) that he is addressing, nor is it unrestrained corporate power (them). More fundamental, giving rise to both of the above polarities, is the almost unquestioned commitment to growth that is built in to most of our systems. In Monbiot’s words:

” The promise of private luxury for everyone cannot be met: neither the physical nor the ecological space exists.

But growth must go on: this is everywhere the political imperative. And we must adjust our tastes accordingly…

A global growth rate of 3% means that the size of the world economy doubles every 24 years. This is why environmental crises are accelerating at such a rate. Yet the plan is to ensure that it doubles and doubles again, and keeps doubling in perpetuity. In seeking to defend the living world from the maelstrom of destruction, we might believe we are fighting corporations and governments and the general foolishness of humankind. But they are all proxies for the real issue: perpetual growth on a planet that is not growing.”

One of the most important presentations that I think should be mandatory basic education for everyone is Albert Bartlett’s “Arithmetic, Population, and Energy.”

Bartlett claims that “The greatest shortcoming of the human race is our inability to understand the exponential function.” He talks about the arithmetic and the impacts of unending steady economic and population growth, including an explanation of the concept of doubling time.

Fortunately there is a transcript as well!

http://www.albartlett.org/presentations/arithmetic_population_energy_transcript_english.html

Consider these questions (hat tip to Penelope Whitworth) – “Where does that commitment [to growth] come from? Is it programmed into our genes, or our consciousness, or inherent to biological life forms? Part of the “genetic code” of the cosmos? Is it a sociocultural thing? Could we have a humanity whose value system isn’t around growth?”

I addressed these isssues in my 2015 ITC paper, Patterns for Navigating the Transition to a World in Energy Descent. Growth is a natural pattern that exists in all natural systems. However, some tend to fetishize and reify this pattern as a primary imperative. For many it has become something of a “myth of the given” – we don’t even question it. The first step is to recognize and respect this as a natural pattern, but to realize it needs to be balanced and integrated for optimal health with all other natural patterns (see my brief intro to PatternDynamics: Following the Way Nature Organizes Itself to Deal with Complexity.

In natural systems, growth tends to expand exponentially in the early phase when resources are abundant; then comes a phase of climax, where things can settle down into a more cooperative mode, somewhat approximating (comparatively, and for a period of time) a steady state. The best example is to look at a barren landscape, where fast growing weeds compete with one another for dominance. After a long period of time, this landscape could, under the right set of conditions, eventually evolve into a mature old-growth forest ecosystem, which is a perfect example of interconnected mutual support and reciprocity. This in contrast to the competitive growth pattern exhibited by the “adolescent” patch of weeds.

The question becomes, are humans smarter than yeast, which grows rapidly until all available resources are consumed, followed by a collapse? Can we successfully transition to a climax stage which mirrors the steady-state of an old-growth forest, or are we now near our final climax, to be followed by an unrecoverable collapse?

Even those who question unfettered growth are enmeshed in the system that tends to keep driving it forward.

Integral Economist Peter Pogany saw this commitment to growth as part of the “source code” of the self-organizing world system that emerged in recent history. As systems tend to reinforce and sustain themselves and their dominant patterns, it can be very difficult to try to manipulate and change the system’s direction (see Donella Meadows’ “Thinking in Systems: A Primer”). In Pogany’s view, it will take a (brutal) chaotic transition (which has already begun) to get the system to change course to a new, Gebserian, integral world system that is not wedded to the Growth pattern as a prime directive. Pogany saw this chaotic transition “as a necessity to precipitate a crisis of consciousness that would eventually lead to the wide-spread “integral a-rational” consciousness structure, as based on the thinking of cultural philosopher Jean Gebser” (see my articles Chaos, Havoc, and the American Abyss, and Consciousness and the New World Order.

In my 2015 paper for the Integral Theory Conference (cited above, but also posted here), I quoted from Edgar Morin and Peter Pogany to describe what Bruce Kunkel has called the “cognitive prison habits” that keep us locked in to pursuing endless growth and development at all costs. To requote the quotes quoted in that paper:

Edgar Morin referred to “development” as:

“The master word, adopted by the United Nations, upon which all the popular ideologies of the second half of this century converged…development is a reductionistic conception which holds that economic growth is the necessary and sufficient condition for all social, psychological, and moral developments. This techno-economic conception ignores the human problems of identity, community, solidarity, and culture… In any case, we must reject the underdeveloped concept of development that made techno-industrial growth the panacea of all anthroposocial development and renounce the mythological idea of an irresistible progress extending to infinity” (Morin, Homeland Earth: A Manifesto for the New Millenium, 1999, pp. 59-63).

Addressing this “myth of the given,” Peter Pogany pokes fun at his own profession (of economists):

“Historically, geocapital [matter ready to be used to feed cultural evolution] has registered a net increase; additions and expansions more than offset exhaustions and reductions. This long-lasting successful experience led to the culturally ingrained confidence in the possibility of its eternal continuation. Economic growth theory keeps “deriving” the same conclusion over and over again: Optimally maintained economic expansion can continue forever. Translated from evolutionary scales to our own, this is analogous to “Since I wake up every morning I must be immortal” (Rethinking the World, 2006, p. 118).”

I suggest we join Morin and Pogany in renouncing the irrational exuberance that expects irresistible progress and economic growth extending to infinity. To break out of this cognitive prison habit may be very challenging indeed. However, at some point there will be no choice. It’s time to stop digging that hole that we think is taking us up the mountain.

“These three videos are the culmination of my life’s work to-date and, by far, my most important legacy contribution.”

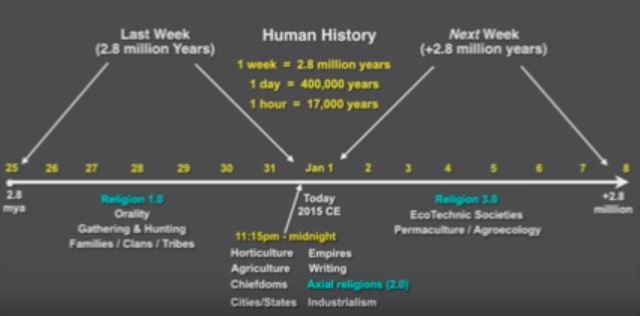

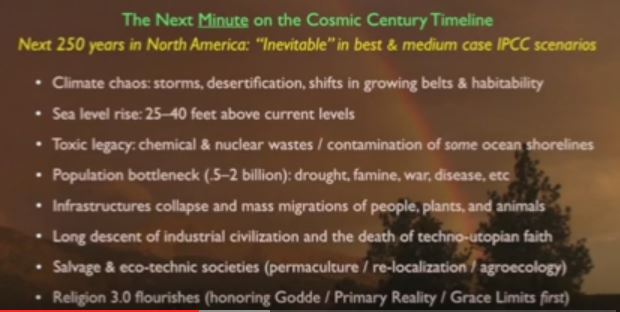

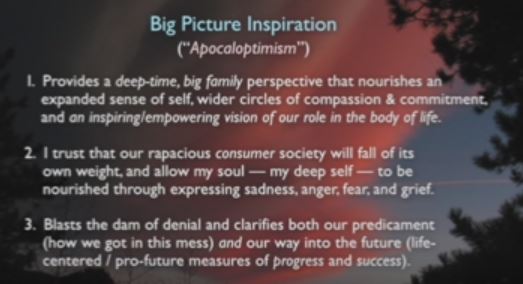

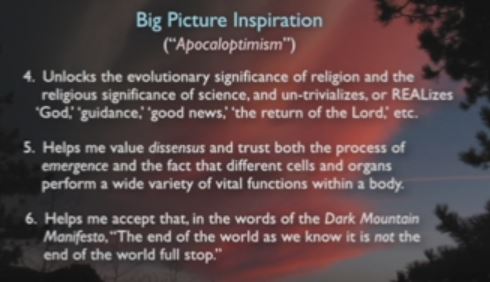

“These three videos are the culmination of my life’s work to-date and, by far, my most important legacy contribution.”  What is ‘Apocaloptimism’? Michael Dowd first heard

What is ‘Apocaloptimism’? Michael Dowd first heard