by Peter Pogany

This story was written in December of 2010 by Peter Pogany. In his last published work (Havoc, 2015), Pogany shares a shorter version of the story, and introduces it this way:

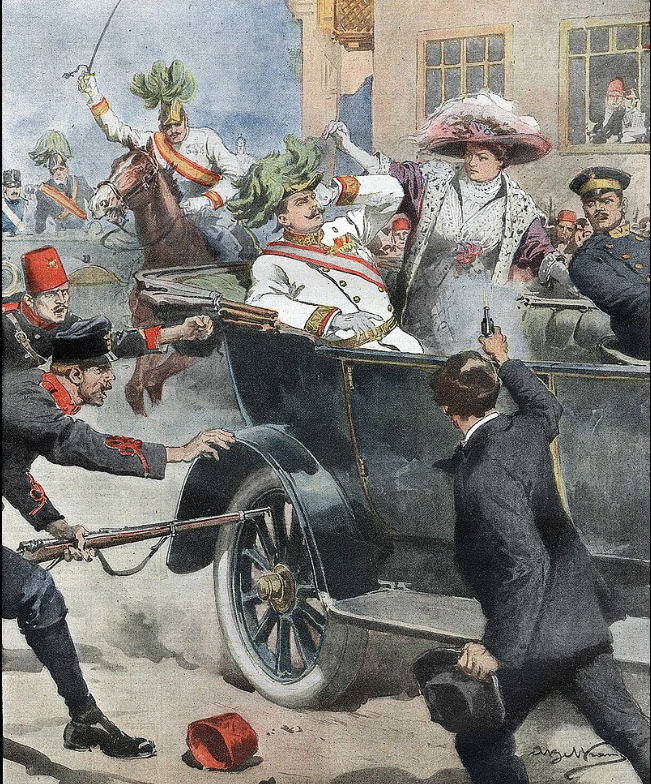

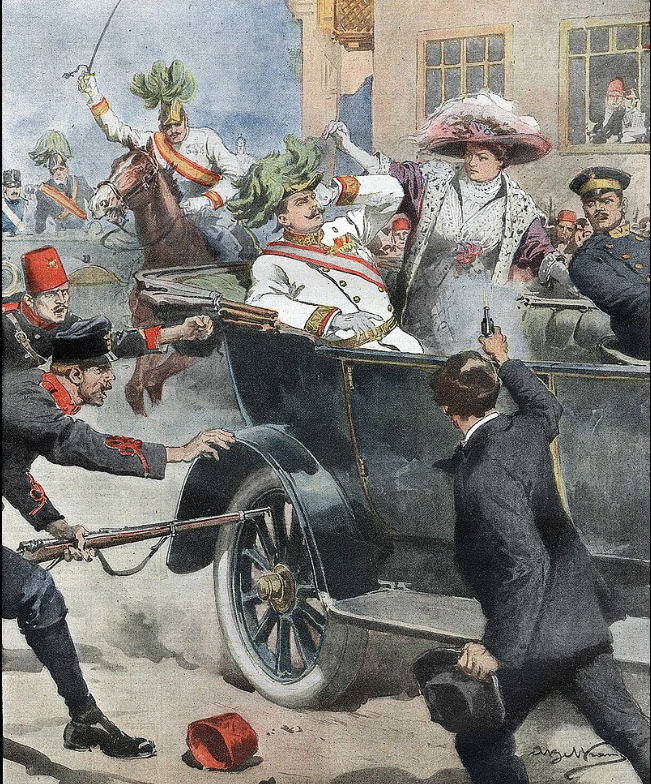

“Chaotic transition is near when the established order becomes prone to disruption through stochastic developments. This characterization corresponds to the ‘butterfly effect’ as initial condition sensitivity has been nicknamed in the study of nonlinear dynamics. How an innocuous and totally unpredictable small event on the molecular/atomic level escalates in significance may be illustrated by the assassination of Archduke Francis Ferdinand, heir apparent to the Hapsburg throne, in Sarajevo, on June 28, 1914.”

Peter Pogany passed away in 2014, but were he alive today he surely would have noted the similar circumstance playing out before our eyes now. How did a coronavirus transfer from bats and pangolins to humans? What started off as a seemingly small event occurring in a seafood and meat market in Wuhan, or a small mistake made in a Chinese bio-research lab, has resulted in bringing the world to its knees. A world already poised on the edge, vulnerable to innumerable innocuous occurrences that could set in motion a chain of events that would instantiate a chaotic transition. A bifurcation that just might bring the existing world system to a transition point. A transition to what remains to be seen. Pogany again: “To put it crudely, something will set the ball rolling, perforce.” I hope you enjoy the true story that follows, and how Pogany tells the tale. Following the story is an analysis, and then a warning! For more, see my Peter Pogany page.

June 28, 1914. Archduke Francis Ferdinand, heir apparent to the Hapsburg throne and his expectant wife Sophie, visit Sarajevo, capital city of Bosnia-Herzegovina, a province of the late Austro-Hungarian Monarchy. Seven potential assassins await them, lined up along the expected route of the official motorcade according to the contingency principle — if A fails B will act, and so on.

Tragicomic coincidences almost turn the plot into a ridiculous failure. One of the conspirators throws his bomb. He hears the explosion, dutifully bites into his cyanide capsule and jumps into the nearby Miljacka River. What he did not know was that the bomb bounced off the Archduke’s car and exploded under the next one; that the cyanide was years past its “due date,” and the river that was expected to swallow him — as would befit a martyr and legendary hero for his people — was about three inches deep at that time of the year. The rest of the conspirators did not act. They either thought the deed was done or became paralyzed in the critical moment. But just when the whole thing looked like a youthful blunder, randomness came to the aid of Big History.

One of the conspirators, Gavrilo Princip, who skipped dinner the night before, got hungry and decided to sample the delicious offerings of Moritz Schiller’s delicatessen downtown. In the meantime, the Archduke — defying counsel to get the hell of out town — insisted on going through with the originally scheduled program, even extending it with the PR gesture of visiting the military hospital where the victims of the earlier bomb explosion were treated. General Potiorek, the governor of the province, decided to speed up the convoy by taking the unencumbered, freeway-like “Apel Quay” along the river. He told everybody about the route change except the chauffeur who drove the car in which he sat along with the royal visitors. It ended up alone in the narrow downtown street where Schiller’s establishment was located.

What is this? We have taken the wrong way!” yelled the General. The chauffeur immediately stopped and began to back up as a crowd of onlookers gathered. Gavrilo, now in the front of the restaurant, found himself face to face with his targets. He pulled out his pistol and killed them point blank. As is well known, the ensuing chain of diplomatic events led to the thundering “Guns of August.” The First World War was on, and from our contemporary perspective of universal history, one might say that the global society entered a period of chaos that did not subside until the end of the Second World War.

But once we appeal to chaos theory to explain what happened during the first part of the 20th century and why, we must account for the butterfly effect, the nickname of “sensitive dependence on initial conditions.”

Since it is defined metaphorically as “insignificant/significant” (i.e., an innocuous happening unleashes a process that results in a major event), the assassination described obviously cannot be compared to the fluttering of the butterfly’s wings. While no direct and inexorable causality can be shown between the assassination and the ensuing conflagration, the occurrence defies the degree of insignificance stipulated by a general understanding of the butterfly effect in the context of “initial condition sensitivity.”

The problem with the application of this concept to historical narrations is that visible events range too freely between what is truly negligible and quite significant. Therefore, to find the real innocuous, totally unforeseeable occurrence (inviting even the notion of being external to human affairs as these can be recognized by simple observation), we must go deeper into matter than what individuals and their actions represent. We must enter the brain, the neurophysics of forming thoughts, making determinations, and instructing the body to carry them out.

In these terms, one might say that the nearly infinitesimal material conditions that allowed a predetermined plan (already established in the assassin’s neural network) to find an opportunity of implementation, resided in a random coincidence between two electrochemical events: One that signaled hunger for the assassin (especially for the offerings of Herr Schiller) and the forgetfulness of the General to instruct his driver about the change of route.

But a short reflection suffices to recognize that this explanation is also unsatisfactory. An uncountable number (e.g., unknowable from the human standpoint) of conditions had to come together for those two cerebral manifestations in order for the event to occur: the weather, the traffic pattern, the speed of service and portions served in the restaurant, the configuration of the crowd gathering around the royal vehicle, and so on ad infinitum. Thoughts in the General’s head that diverted his attention also corresponded to physical circumstances with an infinite number of attributes and antecedents.

To exit from the labyrinth, the initial conditions must be described in more general terms. The inquiry leads deeper into matter; into the world of molecules, atoms, and subatomic particles that make up the human population and bind it with its surroundings. And we can go even deeper (almost incomprehensibly more so) if we accept the stipulations of “string theory,” the most supported version of the “theory of everything” among physicists. Whether we stop at the subatomic level or opt for strings in imaging initial conditions that prevailed on June 28, 1914, the analysis finds itself face to face with the old dilemma of chance versus necessity.

To show that the outbreak of violence ought to be ascribed to destiny rather than to a random incident, we need to make a detour through the realm of historical systems analysis.

Let us begin with a widely acknowledged observation: The Great War effectively ended the age of classical capitalism.

After a very painful — almost revolutionary — start in the British Isles during the 1830s, the institutions, organizational schemes, and the repertoire of matching individual behavior that characterized “Capitalism 1.0” spread to the rest of the world like wildfire.

Smoke-belching factories, squalid living conditions, disease and deprivation, crude exploitation, child labor, injustices of all conceivable forms on a mega scale, Marx’s Communist Manifesto mid-century notwithstanding, by the 1880s, the system turned into a roaring success. At least in broad statistical terms. Per capita income increased for the world’s growing population. International trade and other forms of cross-border economic relations accelerated with a vigor that reminds us of the late-20th-century burst of globalization.

Scientific-technological development brought new marvels every year. Just a few examples (cited from the work of British historian Neville Williams): 1880 saw Andrew Carnegie’s first large steel furnace; in 1881, Louis Pasteur used vaccine to fight anthrax (a method that is standard practice even today in preventing the from-animal-to-human spread of this vicious disease); and so on, year after year.

No sooner did the Victorian era, which cradled the golden age of laissez faire capitalism, die in 1901, the Edwardian period was born and the triumphant march continued. Cumulative breakthroughs in industry and transportation created fabulous new opportunities for entrepreneurship and employment.

The middle class grew by leaps and bounds; especially in the industrialized countries; but even in far corners of the planet, an increasing number of people began to have access to luxuries by the epoch’s standards. Arts, music, literature, and theater flourished. There was no let-up in epochal achievements, not even on the eve of the disaster. In 1913, Niels Bohr discovered the atomic structure; in the spring of 1914, Canada completed its Grand Pacific Railway. It seemed that humanity was on its way to New Jerusalem. And yet, the machinery that wove the fabric of growing welfare became hopelessly outdated by virtue of being less and less able to accommodate further progress. There were four main reasons:

(1) Dependence on gold limited the supply of money that must expand in order to sustain growing levels of output, hence employment and income; (2) while industrialization reached the level at which national economies were prone to accelerate and decelerate if left on their own, the global order’s policy space did not include instruments (i.e., modern fiscal and monetary policies) to counter this phenomenon; (3) the system skewed distribution too much in favor of capital at the expense of labor, thereby constraining the development of mass consumption/mass production; and (4) it was unfit to accommodate institutions or schemes for international cooperation, required by growing economic and financial interdependence among national economies.

“Initial-condition sensitivity” (i.e., proclivity to the butterfly effect) hid in the incongruity between system parameters and the state of the world. Starting with the circumstances that coalesced in Sarajevo on June 28, 1914, any innocuous development (such as coincidental neuro-states in the brains of Potiorek and Princip) was sufficient to tear apart global organization. Why was chaos needed? Because the system was too entrenched and much too successful to abandon it voluntarily via thoroughgoing, peaceful reforms, and because there was no consensus as to what the next global system ought to be.

To allow history to move to “Capitalism 2.0”, which we have been enjoying since the end of World War II, global self-organization needed help from the “outside.” It got it from there since conditions deep in matter, where the state of the world actually resides, can be considered “other than us,” by virtue of being external to the strictly human-scale realm of political movements, personalities, logically explained and plausibly demonstrated individual and national aspirations, ideas and propositions.

World population was fewer than 2 billion in 1914 — roughly the same as the increase between the late 1980s and now, when planetary occupancy numbers around 7 billion souls. It is clear that the standard of living currently enjoyed by billions would be inconceivable if Capitalism 1.0 had remained in force. It had to go. Therein lurks the necessity of its being blown away by something, anything that could unleash the dark forces of the night, the chaotic dynamics from which a fresh dawn, a new world order would emerge after spectacularly failed false starts and a collective moral-catharsis-engendering deluge of blood and pain.

By 1914, the system was so anachronistic that the slightest stir in the organization of matter (intimated in political economic terms as “Capitalism 1.0”) could snowball into an event significant enough to disrupt it, along the same line of reasoning that the flapping of a butterfly’s wings in Mexico could lead to a thunderstorm in France.

Going deeper into matter in analyzing history and considering the human biomass with the world economy a single entity, which since the 1830s has had a demonstrated need for a comprehensive system in order to function and grow, has two advantages.

The obvious one is that such a materialist theory allows us to go beyond personalities and national policies, arguments that tend to provoke dismissals and counter arguments with no end in sight. Since it is abstract, it can exist along with other, more concrete narrative plots and explanations. Indeed, we are learning that reality is much too fuzzy to be describable only through the exclusive application of either/or, hard-nosed binary logic. The good news is that our minds have revealed their capacity to supersede straight-jacket narrow, rationalistic duality. For example, by now, physicists accept that light is both a stream of particles and a wave. Both are correct and they are allowed to live side by side without a formal synthesis.

The less obvious reason may surprise you: Global system parameters are once again out of joint with the times. Namely, the prevalent world order is predicated on vigorous economic growth and it tends to stall, and perhaps even collapse, without it. Marx was wrong in this respect too. He thought that the greatest weakness of capitalism was its inability to accommodate economic growth beyond a certain point. That may have been correct for its first version but it is eminently wrong for the current one.

Judging by the intensification of environmental problems associated with expanding levels of output; along with the expected rise in the prices of oil and other key resources (e.g., several metals) — once the world economy gets back to its full-swing — it appears that nature is trying to tell us something. It may be this:

“Hello earthlings! Considering your huge and growing numbers, coupled with your insatiable material ambitions, I am switching to a constraining mode. It’s time for you to move on and become consciously resonant with my laws. Have you considered Ecological Capitalism (Capitalism 3.0)? Perhaps. But the need to find a substitute for your current ‘expand or perish economy’ faces quite a struggle for acceptance. And admit it: Most of you don’t know much more about it except that it must be something very different. Since the corrective challenge penetrates the wellsprings of your ordinary aspirations, piecemeal reforms are not an option. Your species faces a new spasmodically zigzagging search via macrohistoric chaos. As of now, and increasingly so in the future, you are destined to live with ever-sharpening ‘sensitivity to initial conditions.’ The enhanced sense of unpredictability along with the growing threat of discontinuity you experience means that global society’s rendezvous with another axial date is not far off.”

Remember June 28, 1914! Be in shape!

Sadly, Peter Pogany

Sadly, Peter Pogany